I just couldn’t get comfortable. Every time I turned over, a bamboo slat slipped and cracked leaving me with a thinner and thinner strip of support.

So I figured the best idea was to stay perfectly still. Anyway, it was only a few hours until dawn. Just as I managed to snooze off I heard a distinctive call somewhere above my head, “F*ck You, F*ck You”. I bolted upright and listened carefully. There it was again, “F*ck You, F*ck You”.

Nearby Ian was pissing himself laughing at my reaction to my first encounter with the rare Montana Merkle, a species of bird that has been hunted to near extinction due to a combination of its vulgar taunt, horrible smell and the swastika emblem on its tail.

I did what any sleep deprived male would do in the same situation and yelled back, “F*ck Off!” To which it replied, “F*ck You!”

This went on for some time until finally the frustrated bird disappeared into the night and I counted the minutes until first light.

“Bungalows by Carlos” – with Andrew, Ian and Willie

Moments later I heard movement and looked across the bamboo structure to find my brother was up and he appeared to be collecting firewood. Andrew was muttering to himself, “F*ck it’s cold, F*ck it’s cold”. Funny about that, I distinctly remember him picking the prime spot in the shelter only hours earlier for its cooler aspect. Oh well, F*ck him.

However, he got the last laugh when he built a virtual bonfire inside the hut and almost smoked me out. I gave up sleeping and we all sat around the fire until dawn, listening to Willie Nelson on the iPhone, sharing a tea bag we’d pinched from the nuns a day earlier, in cups fashioned out of Just Juice containers. The subtle orange flavour was enhanced further by the smoky undertones.

By time the sun rose over our half built bamboo hut that we’d christened “Bungalows by Carlos”, we had turned Carlos into one of the great architectural visionaries of our time – the holes in the roof, the dirt floor and the missing walls became an architectural statement. His restaurant that served Maggi noodles out of traditional billy lids and dried peas “Au Natural” deserved its 2 Michelin stars.

A trip down memory jungle track

Here we were stuck in the middle of the jungle; two hours walk from the nearest road, sore and smelly after several days of hard walking in the incessant heat and a cold Coke is looking like a tatts ticket.

Timor will do that to you. I should know, because 38 years ago I was standing in the exact same spot, looking up at my father, blindly following his lead, knowing (if nothing else) that somewhere on the horizon was that promised bottle of Coke.

Back in 1973, my family were on an overland journey that took us across the world, through 16 countries over 2 years. It was an incredible adventure visiting some amazing places, but one country stood out. Portuguese Timor.

Why? Perhaps it was walking barefoot for 120km along mountain paths, the encounter with primitive tribes that had never seen white children, bearing witness to a brewing civil war, my father almost dying of malaria or being chased by a massive buffalo whilst wearing Mum’s dress that gave Timor the edge.

Whatever the reason, the experience left both Andrew and I with a deep fascination, almost obsessed, with a nation that has had a turbulent and tragic past.

Whilst I have an overall understanding of Asia’s newest nation’s history, Andrew, through intensive reading and time spent with the army based in Timor, has an almost encyclopedic knowledge of the events of the past four decades.

My viewing of Balibo the Movie (where Roger East and Jose Ramos Horta follow the same path to Balibo) and a quick read of the latest edition of Lonely Planet’s Timor Leste didn’t quite stack up, but an eight year boy remembers his first big adventure so I had plenty of memories to call on.

Honouring a journey

Ian, our travelling companion, gave me a compelling reason to return to Timor. An emerging writer and former army captain, now living in Dili, he’d heard of our family’s’ story through my brother and wanted to recreate the Timor part of our trip for a book he had in mind.

From day one we had tried to honour the original journey, mindful that a sealed road now covered areas that were formally only mountain tracks.

The first few days involved walking on the sealed road along the coastline. As the only road to the border it was fairly quiet apart from the occasional UN vehicle or motor bike. In the morning, hip hop blaring trucks full of young men on their way to work in Dili would fly past. Those on board just stared down at us with bemused expressions.

We’d walk past villages where the daily catch would be drying on hooks by the roadside alongside hands of bananas. On one occasion, unable to resist an absolute bargain and being banana starved Australian’s, we bought a hand for $2 and gave half back as they were too heavy to carry.

The scars of war

Occasionally, we’d come across an abandoned or burnt out house. The disturbing images of war, rape and bestiality depicted in the graffiti covered walls were a constant reminder of the atrocities that ended just a little over a decade ago.

One afternoon we stopped by a stark eerie lake behind the former Indonesian headquarters. Locals say the place is haunted and I think they may be right. It’s well known that the invaders dumped thousands of bodies inside.

Nearby was the town of Liquica, a run-down almost deserted outpost where the most beautiful of the buildings were now abandoned. We stumbled across the church – the site of a massacre in 1999 – and the derelict building used for the pool scene during the Balibo movie.

Hope for the future

Timor Leste, as East Timor is commonly known, is a country with very few rules and regulations. Security didn’t appear to be an issue so it was natural to camp on the beach.

Within minutes of pitching our tents, a beach that was previously occupied by two goats and an outrigger canoe was swarming with the happy smiling faces of the children of Timor. They asked for nothing, played simple games with stones in the sand or flew their kites made out of rubbish bags.

My iPhone gave them hours of pleasure, each one trying to be Timor’s next top model by out posing each other then shrieking when they saw the result on the screen. The older children helped us collect wood for the fire then doubled over with laughter as they watched our primitive attempts at cooking instant noodles in a billy.

We sang songs around the fire. Shakira’s Waka Waka (This time for Africa) had them all dancing and my rendition of Burung Kaka Tua, an Indonesian folk song that generally only comes out when I’ve had way too many, left them totally perplexed, even though they politely joined in.

Someone told me that the average age of the Timorese population is 14, as I looked around me it was evident as we saw very few people of our age throughout our time in the country.

Hard yakka

The hardest day of the walk started in comfort as we managed to secure a room at a religious retreat run by Carmelite nuns. The sounds of Ave Maria during breakfast put us in a relaxed state for the walk ahead – the crucifix overhead not deterring us from borrowing a couple of tea bags. I guess later that day the stolen tea bags proved to be a salvation.

The day started well. Using some detailed (although a few years old) topographical maps we plotted the same route that we’d taken all those years ago. The country was much dryer than I remember. It felt more like the Australian bush than the jungle of my childhood recollections.

Hour upon hour we walked uphill, the ridgeline never appearing any closer. As we passed villages, locals would wave from doorways, their faces lit up with beetlenut stained toothless grins. The higher we climbed the path would disappear or we’d choose the wrong fork and end up having to backtrack.

On one occasion we ended up deep in a gorge, amongst the rainforest from my childhood. We stopped at a creek where we split up. I went upstream and Ian downstream, whilst Andrew waited to rest his feet that were covered in blisters from his Army issue boots.

I climbed as high as I could until the gorge ended in a sheer rock face with no clear path to the top. Looking back I could see that Ian had run out of options downstream. Andrew, in the meantime, wearing long pants and an oversize white long sleeved business shirt, had removed his ill-fitting boots and was inspecting his battered feet on the beetlenut stained rocks.

You’d think that with his years of trekking experience he may have worked out more suitable attire. By now his shirt was a light shade of brown and we decided that in the new Dulux colour range it would be henceforth known as “bespoke white”.

The diversion into the gorge cost us several hours. It was clear by now that a lot had changed in 38 years so we went back to navigating the way our family had. At each village we asked locals for directions, where they would all disagree, and we’d go with the elders view.

Miss Portugal

On one occasion we met a “hot” (assessment made by three grown men who had just walked eight hours after sleeping in a nunnery) woman who had returned to Timor to retrace her roots. She was wearing a tight clean Nike T-shirt, looked in great shape and had this radiant glow – everything about her was in stark contrast to her surroundings – including us.

Despite this we stood tall, but only managed to extract that she worked in security in the president’s office before her boyfriend drove us away with his snarly demeanour. Andrew looked shattered, not comprehending why his impressive use of Spanish with a Portuguese twist and rugged intellectual look had got him nowhere.

In her defence “Miss Portugal”, as she consequently became known, did dispatch a couple of her relatives to lead us back on the path. After an hour of bush bashing we were led to a clear track. To thank them we gave them both a small amount of money, to our astonishment they got down on one knee and kissed our hands.

By now though it was getting close to sunset and evident that several of the villages on the map no longer existed, replaced instead by graveyards. Did the villages move to the coast when the road was built, or where they wiped out during the Indonesian occupation? Who knows? We made the decision to bed down fifteen minutes before sunset.

At that exact moment we came across a half built ramshackle hut with a view down the valley. Pinned to the side was a photocopy of a friendly looking face and the word “Carlos”.

The march to Batugade

At first light we bade farewell to our luxurious accommodation and scrambled down the valley until we reached the road. From here it was only a couple of days walk along a flat road and the beach to the border town of Batugade.

The final day was a beautiful walk along the black sand beach, collecting shells and singing the 59th Street Bridge Song by Simon and Garfunkel, which my sister taught me on this very same beach in 1973.

By now we had the rhythm going and were striding along at a good pace until I asked why there were Indonesian flags on several houses. Oops! We had walked 2km past our destination into Indonesia. Sheepishly we sauntered back along the road, stopping at a stall for a can of ice cold coke before cheekily stepping over the border chain with a wave to some nearby immigration officials. Seems that finally after all these years the tension may have eased between the co-habitants of the island.

Balibo – dark past, brighter future

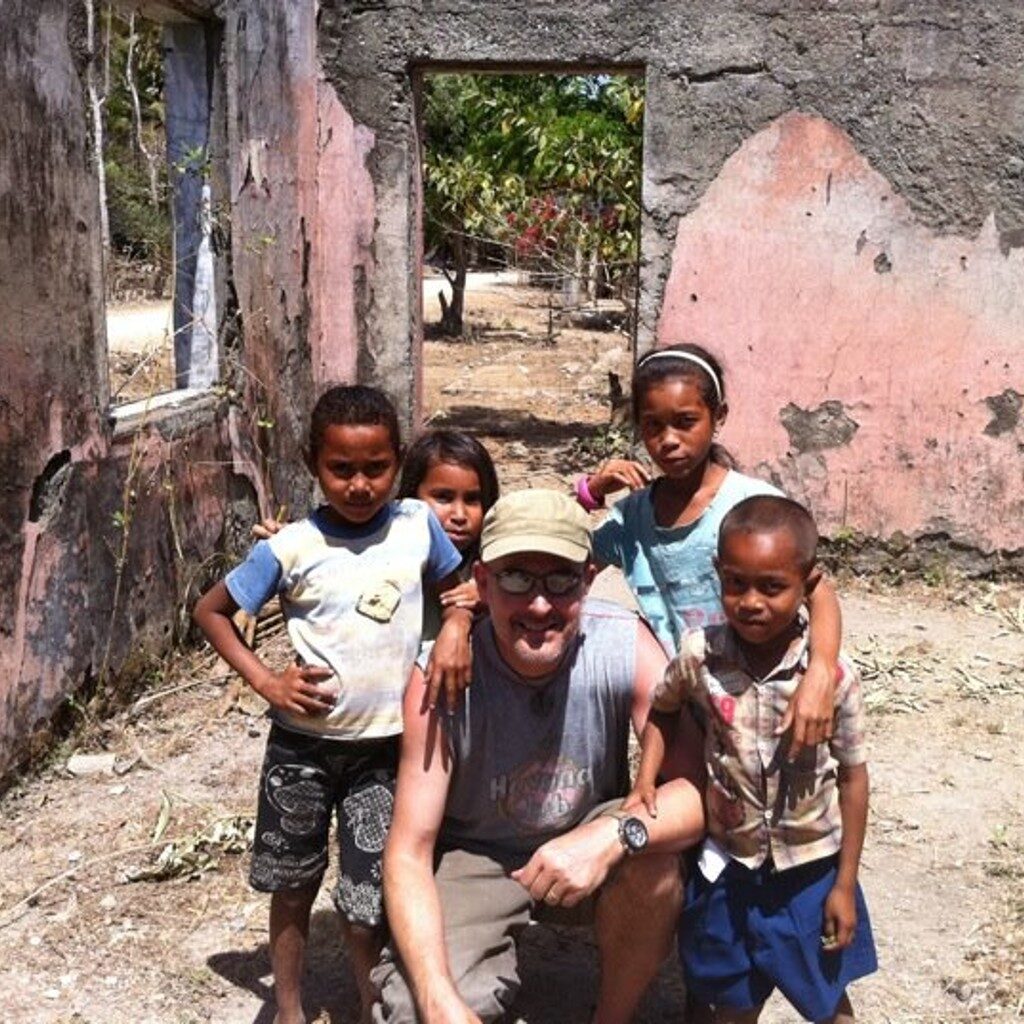

The script says that we were supposed to walk the final 14km steep climb to Balibo, but hey, it was really hot, we were tired and we had a four wheel drive on call. I asked our driver to drop us off 50 metres out of town so I could walk the last few steps barefoot. As we emerged over the hill we were mobbed by kids keen to show us around.

Balibo is infamous for being the place where five Australian journalists were murdered by the Indonesians in 1975. There’s not much left, other than a small community centre that stands as a memorial and an old Portuguese fort.

Several abandoned buildings surround the square and one grabs your attention above all others – the one riddled with bullet holes. The children are keen to pose for photos against the walls. One of the girls insisted on making the sign of a pistol in every photo, her defiant expression contrasting that of her bubbly friends. Disturbed by this I showed her how to do the peace sign and with it her expression changed and a smile crossed her face.

In the hands of these children Timor has a bright future.

Copyright © Reho Travel 2025. All rights Reserved