An epic mountain bike race through the wilds of East Timor

Sore Nuts

The pain in my groin is starting to become unbearable; with every turn of the pedal I wince and try to shift my focus back to the road ahead. Just behind is the constant rumble of motorbike and truck engines, I can feel their gears as they change up and down dependent on my speed. When I’m feeling good, they bring me joy, like I’m conducting an orchestra. This is not one of those times. I’ve only been on the road for an hour today and already the pressure is building and wearing me down. I look down at my Garmin and decide that I will push on for another kilometre before a well-deserved stretch and rest.

The road snakes ever upward, but thankfully, levels out slightly and miraculously turns into smooth wide bitumen as we approach a picturesque, yet, crumbling town nestled in a green valley between two mountain passes.

As I near the corner I hear singing just up ahead. For a minute my legs find something extra and I enter the straight to find a choir of dozens of school children singing for me, resplendent in their freshly pressed bright yellow uniforms. I don’t know what the song is about, but I imagine that it is a celebration of freedom.

Further up the road, as far as the eye could see, were locals three and four deep, just standing patiently, silent, respectful. It was all too much and, not for the first time in this race, I signal the crew to stop, as I get off my bike and break down in tears.

Suddenly the singing stops and a hush goes through the crowd – oh no they think I am giving up! I carefully walk across to a group of young guys, point to my groin, do a quick adjustment and say, “Sore nuts” several times until they roar with laughter and start yelling out “sore nuts!”.

I look back down the road at the long line of support vehicles filled with doctors, nurses, police and officials and decide they deserve a show too. Something comes over me and before I know it my inner Miley emerges and I start twerking in the middle of the road. A ripple of applause runs through the crowd and before I know it they are cheering wildly and, behind me, horns are honking incessantly.

Fully energised, I jump back on the bike and spend the next kilometre high fiving anything with a pulse, even a confused looking goat. It’s day four and suddenly the 39km climb ahead of me isn’t looking so difficult. I start to answer the question that’s been running around in my head all week. “What am I doing here?”

The Race

I have a love of Timor that goes back to my childhood when, as a family, we spent some time travelling through what was then a forgotten Portuguese colony. The trip concluded with a week long walk to the now infamous town of Balibo.

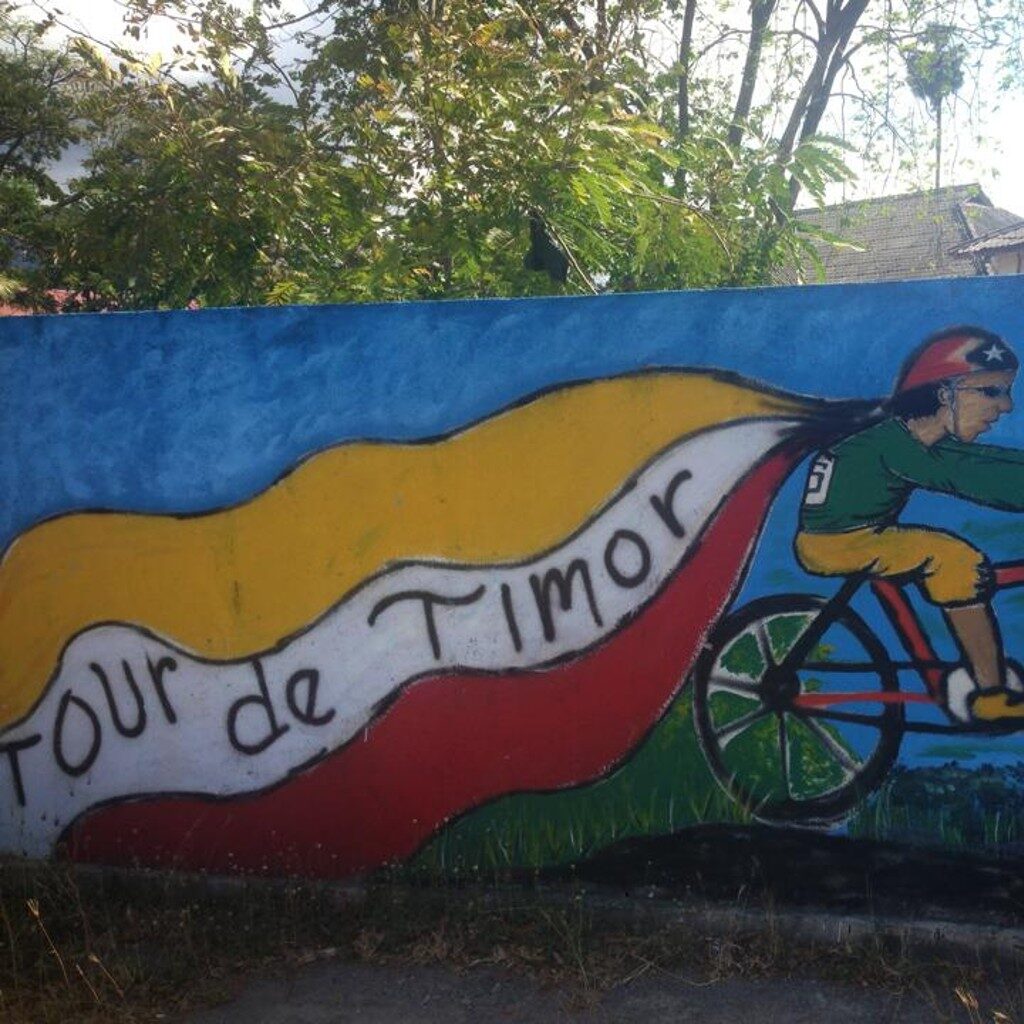

I returned in 2011 to revisit that walk. Along the road I noticed small Tour de Timor signs and assumed that riding a bike would be easier than walking. So here I am. And how wrong I was.

Originally the Tour de Timor was an initiative of national hero and former president José Ramos-Horta, as part of his peace-building and nation-building campaign. Now in its fifth year, the 2013 event comprises of five-stages over five days, covering 473 kilometers of Timor Leste’s best and worst roads.

The race attracts all sorts of riders, from seasoned international professionals to eager locals and weekend warriors. The one thing they all have under their belts is a lot of mountain bike experience.

Our “Fit to Travel” team consisted of my workmate and seasoned road rider, Nickola Hoffmann, my fit and flexible personal trainer, Marissa Frew, and myself, a nearing 50 year old, who was in pretty good shape, but hadn’t put peddle to metal – or crutch to bike seat – in more than 30 years.

In fact, none of our team had ridden a mountain bike until this year so we were on steep learning curve. Every weekend through the winter we’d trudge up to Lysterfield National Park and slowly build up our experience, improve our skills and get the miles in the legs. However, nothing in Australia could have prepared us for the searing heat, gut-wrenching uphills and life threatening downhills of this race.

Dili

A couple of days in the capital city, Dili, were useful in preparing for the race. A ride up to the Jesus statue on the outskirts of town helped us aclimatise, get to know a few riders and visit the sites.

Everywhere we trained we were given respect on the road. Before we knew it we were confidently weaving between trucks and buses along the main street swathed in Tour de Timor banners. Locals would come out of their houses, big smiles on their faces, wishing us luck and say “Thank you” for visiting their country. This theme continued throughout the race. People would yell out thank you and you’d do your best to say thank you back. I mean they were the ones standing in the sun for hours to support you.

I took the girls to Santa Cruz Cemetery, the site of the 1991 massacre that is renowned as the turning point of the independence struggle. We just stood there, unwilling to communicate our thoughts, pushing our minds to imagine what it must have been like. At the same time, unable to take our imaginations to such a dark place.

Reality Hits

Already the first day is a blur. I remember my tummy churning as the riders milled around the start, a cool sea breeze coming in and armed guards surrounding the presidential palace. Then the starters’ gun went off and, within minutes, I was pedaling furiously, but had lost all the other riders and was stone motherless last.

That’s right. Within one kilometre I had been burnt off by every other rider. The guy with one leg, several clearly overweight riders, locals on dodgy bikes. Even my teammates. I remember thinking, well this is my new reality and I just need to focus on riding my own race. My goal was to complete every leg and I wasn’t going to let any smarty-pants experienced riders intimidate me.

While it was a long day, overall the road was good and, the last 20km aside, generally flat. It was the 40 degree heat and strong headwind that slowly wore me down. Many times I was ready to give up, but then caught up to several riders and we rode the long straight stretches as a team which, if nothing else, kept me focused and held my concentration.

Walking up hills really plays with your mind, as you realise that your legs are simply not capable of pedaling. On the other hand, it restores your energy and makes you look forward to getting back on the bike.

Riding the last few kilometres into Baucau I was accompanied by a massive sense of accomplishment. After nearly eight hours on the road, I was on a fast smooth downhill, past waving kids crumbling pink colonial buildings and, at the end of a straight, a blue blow-up archway that sucked me through in a blur, tears streaming down my face. Someone handed me a banana, a nurse poured water over my head and I drifted off in the massage tent to the distant sounds of Bob Marley’s Buffalo Soldier as three girls simultaneously punched and pinched my screaming muscles. Damn that felt good!

Are you serious?

Day two started with a steady beautiful winding road through the foothills, shaded in part by eucalypt forests interspersed with lush groves of palms. Children lined the roads, the temperatures were cool, and it was mainly smooth bitumen. Now that’s what I’m talking about! I found new legs and easily passed several riders.

Suddenly, as I was gaining confidence and having the time of my life, it all changed. That smooth bitumen was replaced by a steep, rocky, slippery path that went on for nearly an hour. Are you serious?!

I was terrified, even in training I’d have to hold my breath to get past a few metres of terrain like this. I gripped the handlebars tightly, straightened my arms, pulled my body behind the saddle and slowly descended. I wouldn’t allow my mind to do anything except concentrate on the elements ahead of me, searching to find the safest line and, having experienced a bad fall in training and learning a hard lesson, never, ever looking down.

Forearms throbbing, legs screaming, I somehow made it down and was confronted at the bottom by a small river crossing. I inched through the water, worked up the slope, just as my wet tyres slipped on a rock, and slammed into the road. Down and almost out I walked up the next hill and, near the top just as I was ready to pack it in, noticed something glittering on the road. It was a silver medallion with a picture of Mary Magdalene on it. I slipped it in my pocket and from that moment knew that I was not alone – maybe those quiet words I’d had to the Jesus statue had resonated higher up.

After getting my first taste of really rough roads, the rest of the day felt like a breeze, despite the steepness of the uphill, the crazy winds and rain that came out of nowhere and the thinning air as we climbed above 1200m.

By now my bottom was becoming increasingly sore. So I fronted up to the medical tent and said, “Who wants to look at my arse?” The nurses gave me one look and went back to eating their lunch. Eventually a brave doctor bent me over and started laughing. “Mate do you have a camera on you, your arse looks like a Japanese flag?” Then he applied some alcohol directly to the wound, the resultant scream could be heard in Darwin.

Heroes

Just when the 4:30am wake up calls, long days of riding and monotonous food start getting to you the beauty of the situation takes over. We were camped in the middle of a football field in the rugged hill town of Ossu, home to resistance fighters and a stunning cathedral that looked totally out of place.

Down below were primitive thatched houses where goats and chickens roamed freely and men sat idle staring up the hill to this strange tent city. For the kids, it was like the F1 Grand Prix had come to town. A simple act like cleaning a chain would have them surrounding you, eager to learn, eyeing your bike like we would a Ferrari.

To these kids we were heroes. They didn’t know I was the slowest rider and I certainly wasn’t going to let on. Now if I was a hero, then Anche Cabral was nothing short of a Rockstar. The leading female rider represented them; she was a local girl from the hills and her flashing smile drew crowds. Everywhere she went kids would gather around to touch her. She represented hope, the future and was already a national hero in a new country that was on a desperate search for role models.

Disaster

Overnight rain had made the road almost impassable. So for the first few kilometres the field sat behind a pace vehicle that kept everyone going along at a safe even rating on the slippery descending dirt road. When I say the field, I meant everyone but me. Somehow my speed was decreed as safe anyway as I didn’t even know what was happening ahead of me.

The morning was cold and wet and just as I was getting used to slippery conditions I came around a corner and immediately my heart stopped. From a distance, I could see a rider down with Nickola bent over her. As I rode closer I noticed Marissa’s bike lying idle, then heard her cry out from behind those who had stopped to help.

She had come down on the corner and was cradling what appeared to be a broken arm. Within minutes, the ambulance was there, we had her on a gurney and I remember scrambling in the back to find blankets to keep her warm while struggling with her shoes, which didn’t want to come off.

The Australian and Timorese doctors worked together to diagnose and treat her injury. Knowing that she was in good hands, it was time to move on and complete this race for her – what more motivation did we need? As Nickola and I hugged it out we noticed a young rider from Darwin just standing there, without a bike. Matt looked deflated, having just loaded his wrecked bike onto the sag wagon. I took one look at Marissa’s bike, handed it to him and said, “C’mon mate let’s smash this race”.

And smash it we did, for the next 107km we carried our bikes for 3km through mud and threw them in a river to remove up to 10kg of mud that was stuck embedded in every moving part. Just when our bikes were ready to seize up I had a McGyver moment.

Every 10-15km we came across a small shop that, if we were lucky, sold Coca Cola. It only took a small nod of acknowledgement from the owner. Our brakes would come on and we’d rush the stall for some of that sweet warm liquid refreshment. On one such break I noticed cooking oil on the shelf. Much to Nickola’s horror, and the amusement of onlookers, I bought 2 litres and poured it all over our bikes. For the rest of the day, as our bodies were getting weary, our bikes were running well like, um, well-oiled machines!

They needed to as we reached the coast. The road flattened out, but potholes the size of cows would fill with water so the road would crumble into a path one minute, then a skating rink the next.

It was now up around 40 degrees with no wind to speak of. So, despite the ocean being only metres away it brought no relief. The trees were far apart and we demanded showers from our entourage every 10km or so. Seriously, how lucky were we? While Adam Cobain and the leading riders were relaxing and tucking into lunch, we had a motorcade of support crew that would materialise with water, bananas and words of encouragement at the wave of a hand.

It’s all downhill

I’m already halfway through Day 4 and it suddenly dawns on me for the first time in the race that I can do this. Just get up this damn hill and its all downhill from here.

Halfway up the hill I catch up to Matt, who has just had his second puncture for the morning. I throw him my spare and continue the grind until I reach Martha, a middle – aged Singaporean woman who has spent most of the race at the back of the field. She is struggling with the cold, so I pull over and force my muddy sweat soaked arm warmers on to her arms that are already covered in goose bumps. I certainly don’t need them as cold, wet conditions put me in my comfort zone.

Despite the altitude taking my breath away, we climb up beyond 2000m and leave the clouds in the valley below. This is seriously rugged country; men with deep lines etched on their faces would huddle on a rock, alone, staring off in the distance, nearby a simple stone house with a primitive cross marked their existence.

The top comes as an anticlimax, no fanfare, just a lifting of the fog and down I go. I’m in extreme pain, but 1700m of gentle downhill makes it all worth it. Somehow Matt has gone past me and I’m back with my entourage, Martha having gone out with hyperthermia at the top, but now sitting comfortably in the back of the ambulance sipping on a hot chocolate.

With 20km to go, I decide to give it absolutely everything and push really hard. The country is truly spectacular, the road is lined with gently undulating rice paddies, and it seems that every man and his dog has come out to watch.

With 10km to go, two police motorcycles pull up alongside with sirens blaring challenging me to go even faster. From that point to the finish I am on cloud nine. The nurses are hanging out of their support vehicles screaming encouragement, horns are honking and, as I enter the town of Aileu, the crowds are getting thicker and more animated, excited by the spectacle.

With 200m to go, and the finish line in place, I spot a rider up ahead and burn every last ounce of energy to catch him on the line. I raise my arms in triumph, channeling my inner Cavendish. Only one day to go. Damn, unbelievably I could seriously finish this race, if only I can stop crying.

The finish

I take a quick look at the map relieved to find that today is mostly downhill. Too easy, bring it on! My relief soon turns to anguish as the day decides to throw every element of the previous four days at me.

On one section Simone, one of the nurses, runs ahead as we push our bikes up a steep incline that seems to go on for hours. I look up at her beaming smile as she lies through her teeth and assures me that the road levels out up ahead. Every moment she is looking more attractive as I do anything to take my mind off the heat, the climb and the pain that is a constant companion.

Only minutes ago the police chief tried to talk me into giving up as, according to her, I am holding up hundreds of commuters that are trying to get to Dili. Interestingly, she’s starting to look pretty good too – hair out, nice uniform. However, an argument entails, so I give her the universal sign and continue my relentless push to the top.

At the summit I take in the amazing view. The road snakes down the steep mountain and reappears in the valley below, eventually reaching the ocean and the main coast road from Liquicia to Dili. I draw a deep breath and start descending one of the steepest and most dangerous roads in the world.

I can’t feel most of my fingers, but my feet are shot and I know that every one of the piles of boulders that make up this bad excuse for a road is ready to end my race. Somehow I push through, buoyed by the fact that I’m not far from the sea and, soon, I will get to ride the familiar coast road that inspired me to be here in the first place.

I turn on to the main road and push the last 20km into a strong headwind with the waves occasionally crashing across the road. By now the road is open. Overloaded trucks come at me from every direction as my police escort valiantly tries to pull the traffic over. Rounding the last corner, I cross to the wrong side of the road and nearly get cleaned up by a bus Unfazed I focus on the finish line, which has already been packed up.

There was no grandstand full of well-choreographed choirs and the marching bands that I expected. Instead, I’m welcomed by my constant support throughout the race, – my teammates and a handful of nurses! As I cross the line I start crying uncontrollably which, apparently, ended 10 minutes later as I ate half a chicken with one hand and embraced the Minister of Tourism in the other.

Every moment was beyond difficult. I spent longer in the saddle than every other competitor and had plenty of time to contemplate how little most of us achieve in our daily grind. The only thing that kept me going as I rode past cemetery after cemetery were the hundreds of thousands of people who have died for freedom in this country. So who am I to complain about a sore arse?

5 Days, 473 kilometres, 9 months training, a lifetime of memories and the support of a nation.

Copyright © Reho Travel 2025. All rights Reserved